Secret diary penned in 1945 and shared for the first time recalls VJ Day memories

Today marks the 80th anniversary of Victory over Japan Day (VJ Day) - the moment Japan surrendered to the Allied forces, bringing an end to six long, brutal years of the Second World War.

Across the country, wreaths will be laid, and a two-minute silence will be observed at 12 noon. At the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, a Service of Remembrance will honour those who fought and died in the Far East.

Secret diary shared for first time

For Wendy Hall, today will be one not only of national importance, but of personal poignance. Her thoughts will turn to her father, stoker Peter Brian Sutcliffe, a 19-year-old from Hyde serving aboard ships thousands of miles from home in the Pacific war sphere, when the news broke in August 1945 as she shares his ‘secret’ war diary for the very first time.

After surviving skirmishes with submarines and witnessing the horrors of kamikaze attacks, his ship was posted to Japan in December 1945, when he got to go ashore, visiting Yokohama and Tokyo.

It must have been a devastating sight to behold for one so young, the fire-bombing of the city earlier that year in March 1945 being the single most destructive air raid of its kind in World War Two, claiming more than 100,000 lives and destroying half of the city.

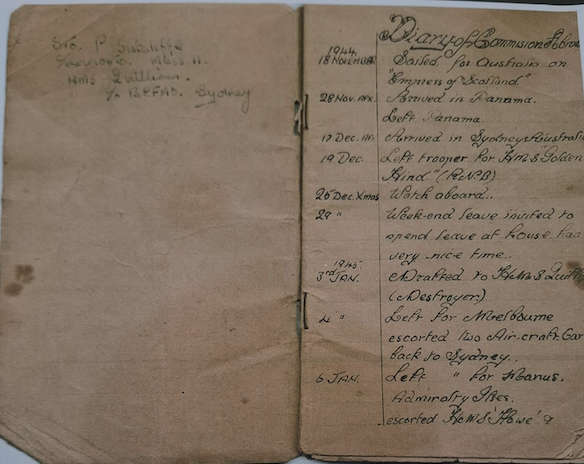

Wendy reveals that her father kept the ‘secret’ diary during his time in the navy, having first volunteered in July 1943.

Diary extract.

She says: “My father was a 19-year-old Hyde lad serving with HMS Anson as part of the Royal Navy’s British Pacific Fleet on August 15, 1945 when Japan surrendered.

“He kept a secret diary during his time in the navy, logging everything which happened while he was on various battleships.

“He sailed 80,000 miles as a stoker in ship boiler rooms, witnessing kamikaze pilots hitting nearby ships and being hospitalised with tropical ulcers to name but two of many other events.

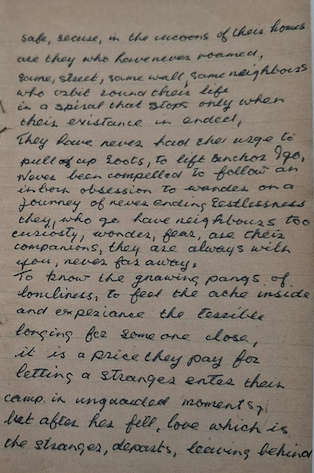

“He wrote a stunning poem about his life as a seafarer, explaining his compulsion to traverse the seas away from home, but the dreadful homesickness that came with it.

“He told me that he wrote it around the time that Japan surrendered as it was a quiet time at sea. It’s particularly amazing that he would have been only 19 at the time,” she adds.

We publish Peter’s poem at the foot of this article.

From Hyde to the Pacific

Peter’s diary entry for November 18, 1944 reveals he was posted to Australia, travelling aboard the ‘Empress of Scotland’ which served as a troop carrier in the war.

The ship itself had survived an air attack just nine days earlier off Northern Ireland, three bombs being such near misses that they reportedly ‘glanced off the ship’s rails and a lifeboat, exploding in the sea’.

Peter travelled to Panama and on to Sydney in Australia, where he was initially based at the onshore Royal Naval Barracks establishment HMS Golden Hind, spending Christmas Day on the other side of the world.

On January 3, 1945 he was drafted and headed back out to sea, serving aboard a number of battleships before joining HMS Anson.

His fascinating diary shares scrapes with submarines and tells of tense encounters when other ships were hit by ‘suicide planes’ - the Japanese kamikazes.

It also includes his own sickness due to tropical ulcers and a quarantine aboard his ship due to a smallpox outbreak.

On May 20, 1945, Peter was serving aboard HMS Quilliam when his diary includes the destroyer’s almost catastrophic collision with HMS Indomitable in thick fog while travelling at 25 knots.

HMS Quillam had been assigned to guard HMS Indomitable - an aircraft carrier - against kamikaze attacks. But instead she accidentally struck the carrier with such force her own bow was almost ripped off, Peter writing: “Heavy fog HMS Quillam collided with HMS Indomitable at 25 knots at exactly 06.35 hours. Bow almost cut away two feet from waterline.” Fortunately there were no injuries.

After nearly being sunk on the Quilliam, the ship was towed to Leyte in the Philippines for repair.

Stricken - HMS Quillam.

Peter was assigned to HMS Anson in July 1945. However, he was on shore leave on August 15 in Australia when the ship was in Hong Kong and Rear Admiral Cecil Harcourt accepted the surrender of the Japanese forces there aboard the vessel.

After the war

Peter was to travel to Hong Kong aboard Anson later that year and his diary recalls how they rescued a number of Chinese from the sea who were travelling in a ‘junk’ or Chinese sailing boat, stricken in bad weather. The diary documents how the crew clubbed together to buy the Chinese they had rescued another vessel.

On November 26, 1945, Peter wrote that they left Hong Kong for Japan, arriving in Tokyo Bay, two miles off Yokohama on December 1. With shore leave he was able to travel to Tokyo where he reveals he saw what would have been left of the Imperial Emperor’s Palace after the city was all but destroyed in the war.

His diary also reveals all the places he was stationed and the distance he travelled, naming the ships he served aboard which took him more than 80,000 miles around the globe.

A love story interrupted, then resumed

Wendy said her father was working as a warehouseman at Jubilee Mill in Dukinfield when he first met his wife-to-be Elsie, before heading off to war.

“Mum worked on the factory floor and dad was in the warehouse,” says Wendy.

He later put a deposit down on an engagement ring when he was in Melbourne, Australia, but never managed to pay the balance before his ship sailed for the last time. But their love story had a happy ending.

The couple eventually married at St Mark’s Church in Dukinfield in July, 1950, and they enjoyed 57 years of marriage together until Peter’s death in 2007, aged 81.

After marrying, the couple lived for a while with Peter’s mother on Ashton Road, Hyde, before moving to a home of their own on Hickenfield Road, Newton, where Wendy was born. The couple had two daughters, Wendy’s mum Elsie sadly passing in 2013.

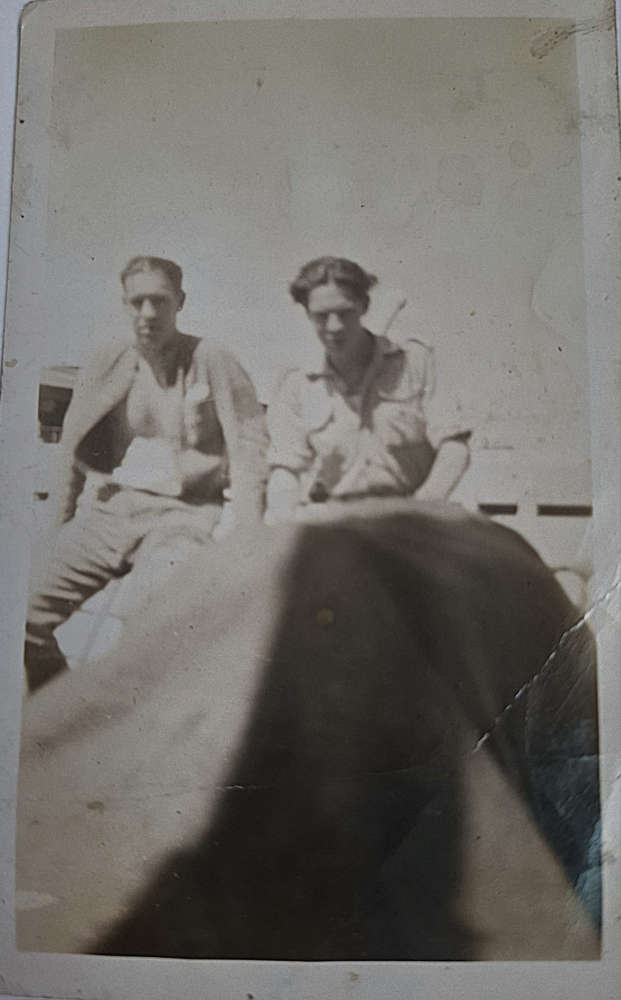

Peter and Elsie.

A Quiet Sea and a Poem

Peter penned the poem below 'around' VJ Day, 1945, when it was ‘a quiet day at sea’.

Safe, secure,

in the cocoons of their homes

are they who have never roamed.

Same street,

same walls,

same neighbours,

who orbit around their life

in a spiral that stops

only when their existence is ended.

They have never had the urge

to pull up roots,

to lift anchor and go.

Never been compelled

to follow an inborn obsession

to wander on a journey

of never-ending restlessness.

They who go

have neighbours too;

curiosity,

wonder,

fear -

are their companions.

They are always with you,

never far away.

To know the gnawing pangs of loneliness,

to feel the ache inside,

and experience

the terrible longing

for someone close -

it is a price they pay

for letting a stranger

enter their camp

in unguarded moments.

But after her fill,

love - which is the stranger -

departs,

leaving behind a hunger

that can only be fed with tears,

which in time

drain away the hurt.

How can the dwellers

know of this?

Peters original poem.

Free fruit and vegetable marketplace for families in Ashton-under-Lyne

Free fruit and vegetable marketplace for families in Ashton-under-Lyne

New estate could be built on farmland in Tameside town

New estate could be built on farmland in Tameside town

‘No one should feel alone’: Local group hosts Endometriosis Awareness March

‘No one should feel alone’: Local group hosts Endometriosis Awareness March

Inclusive football sessions helping local children build confidence through sport

Inclusive football sessions helping local children build confidence through sport