Norma’s strawberry plants are starting to flower. They’re just a small part of a legendary display of flowers the pensioner has cultivated in her garden over almost two decades.

Her garden is her escape when things get hard.

And since her husband John was diagnosed with bowel cancer and kidney disease, leaving her to care for him, she’s needed it more than ever.

Except now Norma and John Heywood are worried they might lose their home – and that cherished garden. Because their landlord is putting up the rent by 20 per cent, almost £180 more each month.

It’s a sum their housing benefits and John’s army pension simply won’t cover.

“We just can’t afford it. We could end up homeless. I feel gutted, just gutted,” Norma tells the Local Democracy Reporting Service. the first time we meet at a neighbour’s home. She fights back tears.

“And I don’t know how a move would affect John. It could kill him.”

Norma and John, both in their seventies, are under an ‘assured/secure tenancy’ – a type of contract commonly used by housing associations, who provide housing for social tenants.

Assured tenancies are supposed to guarantee homes ‘for life’ to those in vulnerable situations. According to housing solicitor Nadeem Vali they ‘provide a degree of stability and protection’ to tenants, in comparison to private ‘assured shorthold’ tenancies.

Unlike under ‘assured shorthold tenancies’ (private rentals), landlords can only turf secure and assured tenants out on very specific grounds that require a court order.

Social housing providers are also subject to tighter regulations on rent increases than private landlords.

As far as Norma, and more than 30 of her neighbours know, they have always been ‘social housing tenants’ – and in many cases, have lived on Gilderdale Close and nearby Napier Street in Shaw for two or three decades.

Many of the residents showed copies of their secure or assured tenancies to the LDRS. and a number of them ‘house swapped’ into their current homes from properties owned by the council or another housing association.

Yet their housing association, Places for People Homes Limited (formerly known as North British Housing), are now claiming the group ‘have always been private’. After keeping rents in line with social rent rates for decades, they claim they want to bring their housing stock in Shaw ‘up to market value rates’.

In February, residents received a letter from Touchstones, a subsidiary company of PfP, who took over management of the properties in 2022. The letter informed tenants of an incoming 20 per cent increase in rent and added that homes in the area were ‘as much as 40 percent lower than market levels’.

“It feels like in one day, we were so happy and content paying our rents, not asking for anything off anybody. Then someone very cruelly just took the rug right from under us and we don’t understand anything anymore,” Pauline Mason, 73, said. The pensioner has lived in her house on Gilderdale Close ever since a ‘house swap’ from a council house 22 years ago.

Pauline hosted a gathering for her neighbours to speak about the rent situation in her immaculately kept living room with tea and biscuits.

But she herself has barely eaten since she received the letter, she admits.

“I saw it and I went to bed. I’ve mostly slept, I just don’t want to face the world,” she confides to the group. Pauline’s hands are paralyzed. She receives disability benefits and support paying her rent.

“At the moment I get my full rent paid. Now they’re saying we’re private tenants? That would mean I have to pay £500 out of my pension. It’s a lot of money. How do I buy food, and electric, and gas?

“I would end up in rent arrears. I would get evicted. I would be homeless.”

And there are more. Joanna and Ernie Ford popped into Pauline’s from down the street. They were also shocked to receive the letter.

Ernie has suffered a brain haemorrhage which affected his hearing, leaving him unable to work. The couple support themselves off his early pension and Joanna’s full time job.

“Really, he needs me at home more to look after him,” Joanna explained. “But the rent increase will mean I have to do extra work instead, taking me away from caring for him.”

“It’s horrible,” Ernie added.

And Susan Sutton, who was one of the first residents to move into the properties after they were completed in 1993, says she spends every minute worrying about what will happen next.

“I’m not trying to be awful,” she told the LDRS. over the phone at a later date, “But sometimes it does make me think is this life really worth it?”

Susan believes she would also have to pay the increase out of her pension and her savings, which she’s carefully put aside over many years so her family doesn’t get saddled with debt to pay for her funeral.

“I know it’s morbid, but you have to think about these things. I’m living with multiple life-threatening illnesses,” she says, listing several serious conditions.

Asked what would happen if she had to move, Susan simply exclaimed “No!”.

“I couldn’t do it. Physically. And I genuinely love my home. It’s lovely. I’ve invested so much of myself and my money into making it a nice place.

“To have to leave here – No. When I leave here, I want to leave in a wooden box. I can’t start all over again. I can’t afford to.”

The room is full of stories like this – vulnerable, often elderly people, many already living on the knife’s edge of their financial situations, who have made a home in Shaw over multiple decades.

While only a small number could make it to the meeting, the group estimates around 14 of the more than 30 households affected would risk facing rent arrears – and possible evictions – if the increase goes through. PfP insists the tenants were always private renters.

But residents refuse to take the situation lying down. Sarah Howarth-Flanagan, 44, has been galvanizing the local community to fight back.

The former teacher, who has experience working in housing, said: “We’re trying to fight. We don’t want to lose our homes. There’s a lot of elderly residents who’ve been here since day dot.”

The mum-of-two transferred from another Places for People property in Ashton Under Lyne, from a two-bed to a three-bed.

Currently a full-time student while she retrains in midwifery, Sarah believes the rent increase wouldn’t affect her as detrimentally as some of the other residents because of her student loan and her local housing allowance.

But she can’t stand to see her elderly neighbours turfed out unfairly.

“It does feel like they’re trying to get rid of us so they can sell the houses or put them up for private rent,” she said.

With the help of local councillor Marc Hince, Sarah and her neighbours are raising the alarm. Together, they’ve mobilised Oldham Council – who would be responsible for rehousing any of the residents made homeless by the rent hike – and are mounting a legal challenge against the housing association with the help of charitable organisations.

After meeting with residents, coun Elaine Taylor, Oldham Council’s cabinet leader for housing, pledged to support the residents and said: “I think what a social landlord is proposing here is reckless and immoral. To potentially make a group of residents who’ve lived there for decades homeless is reprehensible.

“People could end up in temporary accommodation at huge cost to the taxpayer, and as a social housing provider, they know better than anyone how vulnerable people’s housing situations can be.”

Meanwhile Ben Clay, speaking for the Tenant’s Union, described the situation as ‘an outrageous attempt by Places for People to privatise their social housing, impose a huge rent rise, and to override social housing assured tenancies with unfair and unregulated private tenants terms’.

Clay said: “Many residents have lived in these homes, on the same terms, since they were newly built in 1993. This landlord appears to want to rip up their contracts and remove their assured tenancy rights with no consultation, no negotiation, and hoodwink them into accepting unacceptable rent rises.”

He added that the situation was a ‘clear example’ of a growing trend within housing associations, where ‘organisations set up as charities with a supposed social mission, are increasingly indistinguishable from private businesses’. PfP denies these allegations.

Clay is not the only expert concerned about the situation. Social housing academic Stuart Hodkinson at Leeds University added that he thought the case could become a ‘national issue’.

“This is an extremely concerning case that should be a wake up call to the Government about what is happening to social rented housing,” he said. “A housing association that has benefited from large sums of public funding appears to be finding legal loopholes to turn these homes and tenants into cash cows.”

Places for People refuted the accusations that they were trying to ‘privatise’ social rent tenants and maintained the homes were ‘always private lets’. A spokesperson added that the homes had not been built using government grants and that ‘under the terms of the Customers’ tenancies, there is no limit or restriction on the ability of PfP to increase rent’.

A Places for People spokesperson said: “These homes have always been let at market rent and are not social housing properties, but regardless we have always worked hard to keep rents as low as possible. During the Covid-19 pandemic and at the height of the cost of living crisis last year we kept rent increases as low as possible to ensure Customers were not adversely affected by the other financial pressures that were outside our control.

“This has meant that rents have fallen significantly below market rates in recent years, so raising them now is something we must do. Raising them to be in line with the current market immediately would likely result in a significant rise for customers so we are doing this gradually over time.

“We understand the challenges people face and have advised any Customers concerned about the financial impact of the rises in rent to contact us so we can offer support.”

After inspecting residents’ contracts, solicitor Oliver Edwards from the Greater Manchester Law Centre believes there is ‘definitely a legal issue’. He has issued a Judicial Review threat letter accusing the PfP of an ‘unlawful rent increase over and above the amount set by the Regulator of Social Housing’. This would be limited to a 2.7pc increase.

If the increase is ruled technically ‘legal’ in a court of law, Coun Hince says, ‘that doesn’t make it right’.

“For years our council housing stock has dwindled and we were told the gap will be filled by housing associations,” Hince went on. “But do we have enough regulation on these bodies to make sure tenants can stay secure in their tenancies? What we don’t want is housing associations abusing legal loopholes for profit.”

But while political and legal battles are waged over their heads, many residents are simply left feeling uncertain and scared about their future.

“Where would we even go?” Norma asks over the phone. She tells me about the memorial bench she’s built in her garden, to honour her daughter who passed away recently.

The bench, the strawberries she plants for the kids and grandkids that survived her daughter, the garden that keeps her going in the face of so much heartbreak.

She adds quietly: “The apartment blocks where they put you if you’re homeless, I’m not sure they even have a gardens, do they?”

Derker community group recognised for support of Vulcan partnership work

Derker community group recognised for support of Vulcan partnership work

Second man arrested in connection with Manchester Mosque incident with local councillors expressing shock

Second man arrested in connection with Manchester Mosque incident with local councillors expressing shock

Council pushed to do more to support residents without internet access

Council pushed to do more to support residents without internet access

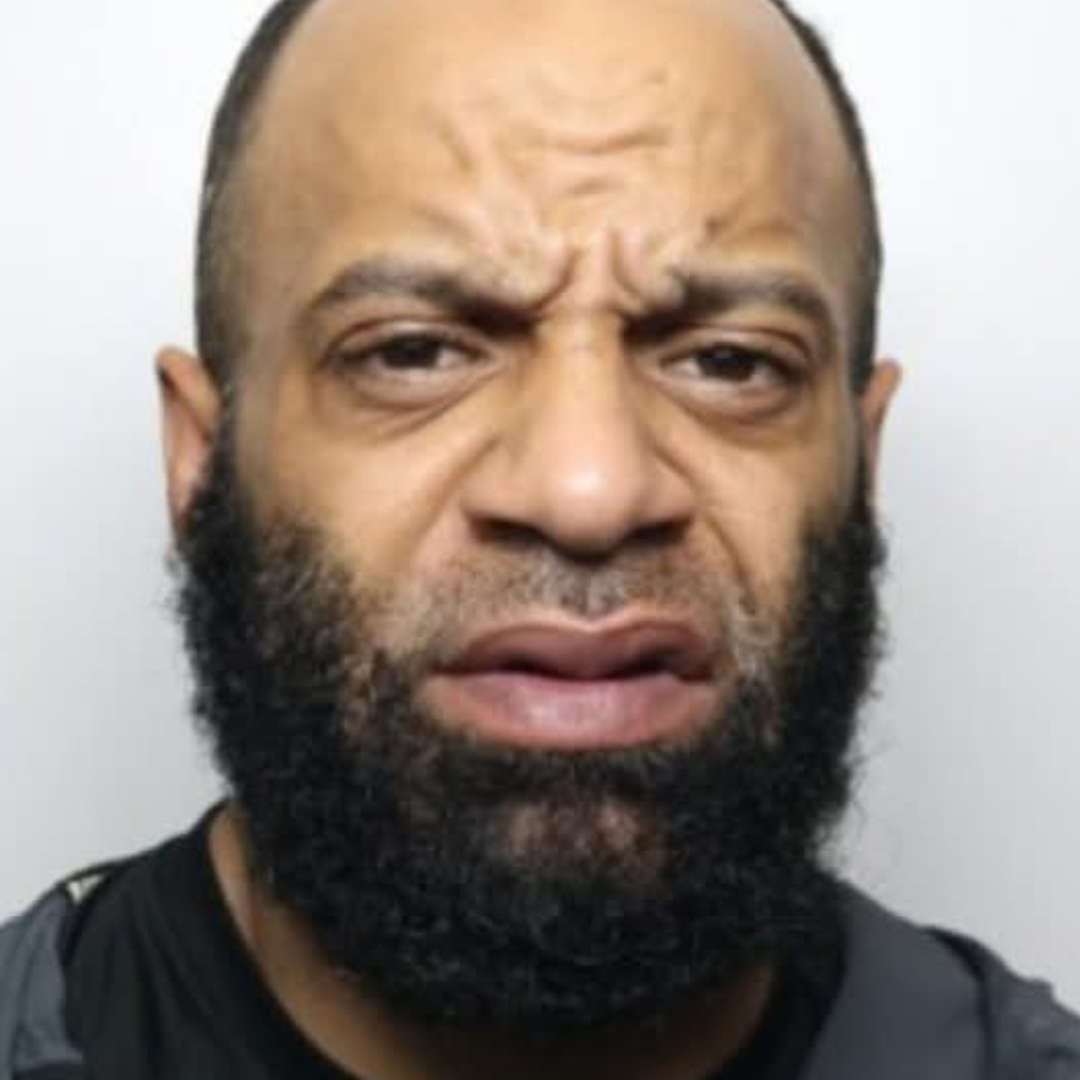

Man wanted on recall to prison

Man wanted on recall to prison